Rule Parser with Golang -- playing with lexical retrieval and reflection

by

This post introduces a project on inventing a parser for application-level service to filter data from its data storage with complicated predicates. For example, a software package manager needs to match the package specification with the client’s information like OS, software version and etc before responding downloading links of packages. Another example lies on Feed product. Clients of Feed product can choose to block some topics they don’t like or resources from some particular authors or sources. These applications all have some predefined domain of rules they need to handle and response to the clients’ requests with data following(or not following) the rules.

Terminology:

In this parser, data is filtered by predicates. To make the discussion easy to understand, here data is defined as context – what kind of items the parser is dealing with, having some attributes describing itself; rules are the description of ideal context the client wants. For example, the video feed application may have the following definition of context:

type Video struct {

ID int

CreateTime time.Time

Tag string

// other fields are omitted here

}And it can handles the rules like

“tag is not comic”

or

“create_time is less_than 10 days”

Here the parser examines every instance of Video regarding the fields of CreateTime and Tag, determining whether they follow the two above rules. The tradition way to do that is to have many if-else statements to handle every field and every rule. But why not make a more elegant design to cope with this need?

Why not to take the advantage of filtering functionality of Databases?

The parser aims to deal with as many various rules as possible to meet the product requirement. It is sometimes too complicated for the databases to deal with these rules like version comparison, or the database can not produce large throughput and low lantency to handle the queries like text searching. The parser lies on the application layer, works after the application fetches data from the data storage system. This helps to decouple complicated constantly updating product needs from data storage architecture. Also it makes data storage design and caching policy more simple. The design of data storage can be focused on how to produce and update data as well as get the data of interest to the clients in a general way, whereas the parser is used to catch up with some customerized needs.

How to use the parser?

Expressive rules:

First of all, let’s define some expressive statements to desribe the rules. As observed, the rules are mostly like this formular “some attribute should work/be like some pattern”. Therefore, an abstraction can be made to describe a general format of rules:

<field> <operation> <pattern>

e.g

tag != `comic`

create_time < 10*3600*24

Where the <field> can be any attribute of the data, <operation> can be any meaningful comparison method and <pattern> can be any corresponding data for the attribute. And in many cases, binary operation are good enough to cover the application needs, including EQUAL, NOT-EQUAL, GREATER, LESS, GREATER-OR-EQUAL and LESS-OR-EQUAL. If more expressive statements are needed, the application can then name an operation for this and define the correct data format for this purpose. In fact, this makes writing a program to parse the statements easy enough and industrial-level programming languages often provide built-in package to handle the plain-text program(as will discussed later, this is just to extract the tokens and run a simple state machine).

How to use it?

It takes a few steps:

-

Input plain-text rules to an instance of parser.

-

Define a mapping between field in the rules and attribute of data schema.

-

Define customerized operations if needed, otherwise basic arithmetic comparison will be performed on field with basic data type.

-

Tell the parser to examine context items one by one with the rules. The parser can tell you whether the context is fully matched with the rules.

More details can be found in the project description.

Technique

This parser is implemented in Go for several reasons:

-

Go is easy to write and publishing its package is easy with git repository.

-

Packages of Lexical analysis and syntax analysis are available.

-

More importantly, Go supports concurrency primitive which makes parsing the rules efficient.

State Machine:

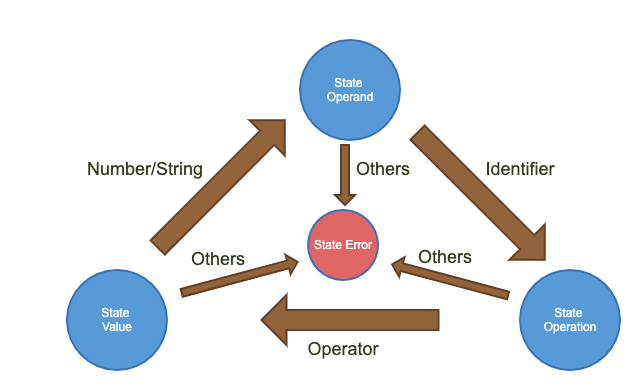

As mentioned above, the syntax of the rules are pretty simple. A simple state machine is implemented to analysize the rules as following:

Therefore, for each statement, the parser only needs to identify the identifier as the field, an operation and the corresponding pattern. For simplicity, the pattern in the rule is presented either as numbers(integers, float) or string. This makes the rule statements complies to Go’s syntax so that packages “token” and “scanner” are used to extract the lexical tokens from the plain-text statements:

type RuleExpr struct {

Operand string

Operation string

Value string

}

type RuleParser struct {

rules map[string][]state.RuleExpr

ruleCount int

}

func rulesParser(rules string) (*RuleParser, error) {

// initializes something else ...

// Initialize the scanner.

var s scanner.Scanner

fset := token.NewFileSet() // positions are relative to fset

file := fset.AddFile("", fset.Base(), len(rules)) // register input "file"

s.Init(file, []byte(rules), nil /* no error handler */, scanner.ScanComments)

var exp state.RuleExpr // here we will put exp into the RuleParser.rules

for {

pos, tok, lit := s.Scan()

if tok == token.EOF {

break

}

newState, err := curState.Run(pos, tok, lit, &exp)

if err != nil {

// get an error from the input

}

curState = newState

// create a rule instance if an end is met.

}

}In the above codes, a new state is generated by the current state with the input token. If the current state can not handle with the token, this means there is an error when parsing at that token and an error is returned. Otherwise, the state machine continues with the new state parsing the next token until it runs out of token.

Since there are three normal states, the package defines a State interface to allow states to exposing the same interface while hiding different parsing details.

type State interface {

Run(pos token.Pos, tok token.Token, lit string, exp *RuleExpr) (State, error)

}

type StateOperand struct {

State

}

type StateOperation struct {

State

}

type StateValue struct {

State

}

type StateEnd struct {

State

}Here a helper ending state is introduced to close a statement. Each state implements State interface and define their own Run method which takes the input from the scanner and generate a corresponding new state. Therefore, when the for-loop keeps extracting token from the rules, the rule instances are generated and be put into the rule parser.

Mapping the fields in the rules and attribute of data schema

This is inspired json encoding and decoding implementation of Go. Annotations of json fields are added as the struct tags of a data structure in Go. Json marshaling and unmarshaling deals with the struct tags. To simplify the use of the rule parser, similar struct tags are added to the attributes of a data structure. For example:

type SoftwareInfo struct {

Sid string `rule:"sid"`

Ver *Version `rule:"ver"`

Channel string `rule:"channel"`

Count int `rule:"cnt"`

}This data structure can match up with the rules like this:

rules := "ver < `3.5.0`;ver > `1.5.0`;ver in `2.5.0,2.5.1`;channel==`google play`;cnt >= -2;f==0"

Extracting the struct tags:

For every data structure in Go, they all consist of zero or more data field. Each field consists of a Type, a Value and some struct tags. By iterating the fields with the help of package reflect, the Type, Value and tag are extracted for each field. If there are some rules mapped to the tag in the rules, examine that rule with the value of the field.

ch := make(chan RuleParserChannel) // this is used to receive the output from the each rule parser

count := 0 // counting the rules

t := reflect.TypeOf(context)

val := reflect.ValueOf(context)

for i := 0; i < t.NumField(); i++ {

field := t.Field(i)

tag := field.Tag.Get(tagName)

if tag == "" || tag == "-" {

continue

}

for _, rule := range p.rules[tag] {

fk := field.Type.Kind()

fv := val.Field(i)

go p.createExamineFn(rule, fk, fv, ch)()

}

}

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

select {

case rst := <-ch:

if !rst.rst || rst.err != nil {

return rst.rst, rst.err

}

case <-time.After(p.timeout):

return false, errors.New("timeout when parsing")

}

}Here is a consideration that the input context struct may be a pointer, so it is necessary to locate the real Element of that pointer in memory before iterating the context by applying Elem() on the pointer, otherwise the we can’t locate the real struct tags with the pointer.

Concurrently examine the rules:

This is just a fan-out concurrent pattern and a timeout is added to avoid the case that one of the rule parser get blocked for too long.

Defining parsing process for each rule:

To simplify the application development, basic comparison of basic data type is performed by the parser automatically. Fortunately all the possible basic data type supported by Go can be enumerated and they can be grouped into string, unsigned integer, signed integer and boolean. The remaining basic data type including array, map, chan pointer, interface is excluded. If the type of a field is signed integer, then the parser convert the pattern of the statement into a int64 and compare it with the value of the field.

But sometimes, basic binary operations can not meet the application needs, customizing operation for a data structure is also provided by the package.

There are also two possible options to do that: One is to override the basic binary operations on a customized data structure. For example, the application can define a Version data structure and define the comparison over it. This is also inspired by the customizing of json marshal and unmarshal of Go. We can define some “protocols” between the data structure and the parser so that the parser can run smoothly by communicating with the data by that protocol. A compare method Cmp is defined by the application over the data structure and it is called when the parser has to perform a basic comparison over a data structure. Here reflection mechanism is used to call the method by name of a Value in Go.

func (ver Version) Cmp(val string) (int, error) {

vs1 := strings.Split(ver.value, ".")

vs2 := strings.Split(val, ".")

c1 := 0

c2 := 0

for c1 < len(vs1) && c2 < len(vs2) {

v1, err1 := strconv.Atoi(vs1[c1])

v2, err2 := strconv.Atoi(vs2[c2])

if err1 != nil {

return -1, err1

}

if err2 != nil {

return -1, err2

}

if v1 < v2 {

return -1, nil

} else if v1 > v2 {

return 1, nil

}

c1 += 1

c2 += 1

}

if c1 != len(vs1) {

return 1, nil

} else if c2 != len(vs2) {

return -1, nil

}

return 0, nil

}

// value.MethodByName(fnName)The other option is to invent a new operation other than using the basic operation over a data structure. For example, the application can define a in operation to find out whether the context’s version falls into a list of versions.

func (ver Version) In(val string) (int, error) {

vs := strings.Split(val, ",")

for _, v := range vs {

if v == ver.value {

return 0, nil

}

}

return -1, nil

}More details about the usage can be found here

Conclusion

It is fun to work with the parsing and lex package of Go and pretty inspiring to borrow some design from Go’s packages implemtation. With the help of reflection, token, scanner, a general rule parser is implemented to handle different kinds of data requirements.

tags: